On the Algorithms That Hear Us

- Kirra Pendergast

- Aug 25, 2025

- 4 min read

This morning, my partner called me from Italy on Signal. He rang to wish me a happy birthday. There was that comforting little delay, the softness of time stretched across continents, between his voice and mine. He was at home in our apartment in Florence, I was writing in bed, sipping on coffee here at my mum's place in Byron Bay.

We talked like couples do when life is moving fast in two directions, his work in Italy and the Emirates, mine everywhere. The countdown to me landing back home after six weeks. He told me about the weekend.

He had gone down to the sea at Castiglioncello, in Livorno, Tuscany, with our friends who have a little place there. Their niece, Elena, was there too, with her boyfriend. Laith explained she is sixteen and wants to become a chef. That part of the story stuck. I said I might bring her back one of my friend Sarah's cookbooks that she wrote, something beautiful, bound in linen, full of photographs of Australia, something a sixteen-year-old aspiring chef would treasure. I asked him to spell her name. Elena. Simple, but I wanted to be sure in case I can get it signed.

We hung up.

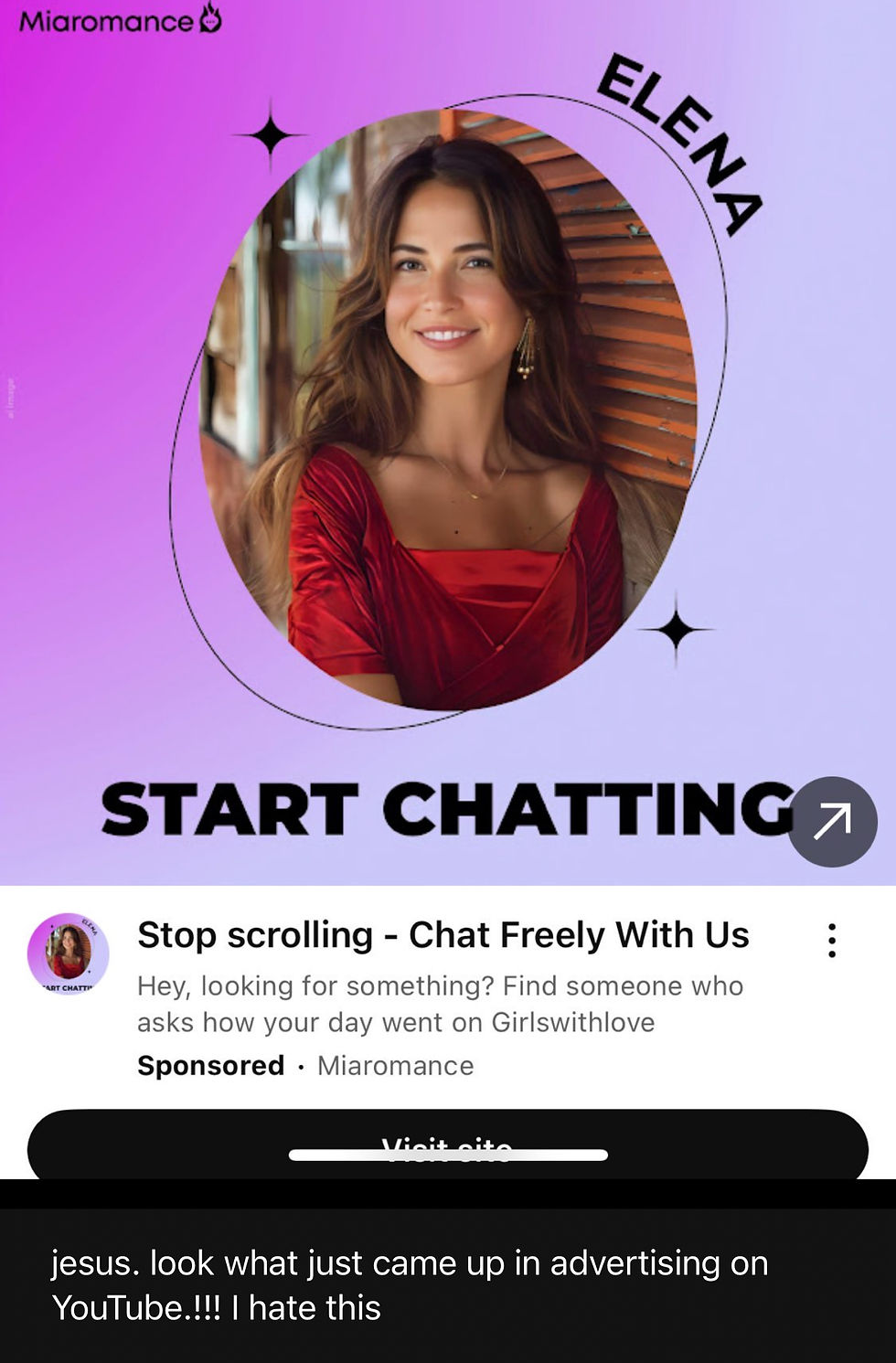

Maybe ten minutes passed. Maybe twelve. And then he sent me a screenshot of an ad that popped up as he clicked on to watch something on YouTube. He was totally creeped out - commenting on why he hates social media so much. There she was, Elena, conjured in the algorithmic ether. Of course she was.

An ad like this doesn’t show up in a vacuum. It’s not random or arbitrary.

Within minutes of a private Signal call, where we discussed a sixteen-year-old girl named Elena, her desire to become a chef, her relationship, and her weekend at the beach, he receives a sponsored ad for a chat app, featuring a young woman named Elena, positioned as emotionally available and digitally accessible.

The ad copy says: “Stop scrolling – Chat Freely With Us. Find someone who asks how your day went.” It is haunting. Creepy. We are meant to think this is harmless. Just data being helpful. The phrase they use is relevance. But in the logic of surveillance capitalism, “relevant” is just another word for “strategic manipulation.”

This is not about Elena. It’s about how your digital proximity to a young girl’s life, your mention of her aspirations, her relationship, was quickly and seamlessly mined, reframed, and sold back to your partner, a 54-year-old man, as loneliness, or longing, or desire. This is sick.

But that’s the story the system is coded to tell him in that moment. Late at night with his partner 16,000km away. He must want more.

More connection. More attention. More women. Even if he doesn't. Even if all he was doing was caring, the algorithm doesn’t care. It cares about the signals. And in this case, that meant a Signal call.

This is what Shoshana Zuboff calls “behavioural surplus”: your emotions, intentions, and micro-movements, harvested and sold off like oil.

That’s the true engine behind these systems: attention. Nothing else. They don’t care about morality. They care about metrics.If you feel creeped out, that’s not paranoia. That’s the correct response. Your inner compass is working.

You are right to be disturbed that this conversation, held on an encrypted line, was still somehow enough to trigger this kind of ad, sexualised, personalised, and emotionally manipulative. This is what it means to live in a world where the walls between private and public have collapsed.

And here’s the sinister part: this happens to children every day. Children who have little to no literacy about how algorithms work.

Not just one-off sponsored posts, but full-blown profiles that follow them across apps.

Profiles that know their anxieties, their fantasies, their searches, their loneliness.

Profiles that guess at what they’ll want before they know it themselves.

Children get hit like this constantly. With content disguised as friendship, empathy, understanding. Influencers who feel like older sisters. Videos that feel like advice and algorithms that know which insecurities to press on, and when. Elena’s generation is being trained inside a machine that never stops watching them.

And the rest of us?

We’re being desensitised. Normalised. So that when this happens, when an ad like this shows up after a call like that, we are supposed to shrug. Swipe. Laugh it off. Say, weird, right? But it's not weird. It's systemic.

Suppose we don’t support the pushback, like the Australian social media age delay, which is one of the first serious attempts globally to draw a legal line around the psychological manipulation of children online.

In that case, we are complicit in the erosion of privacy.

The delay isn’t a silver bullet, but it’s a signal.....that we still believe in boundaries. That not everything a company can do should be legal. That the right to grow up offline, unseen, unprofiled, and unpredicted is worth fighting for.

Comments